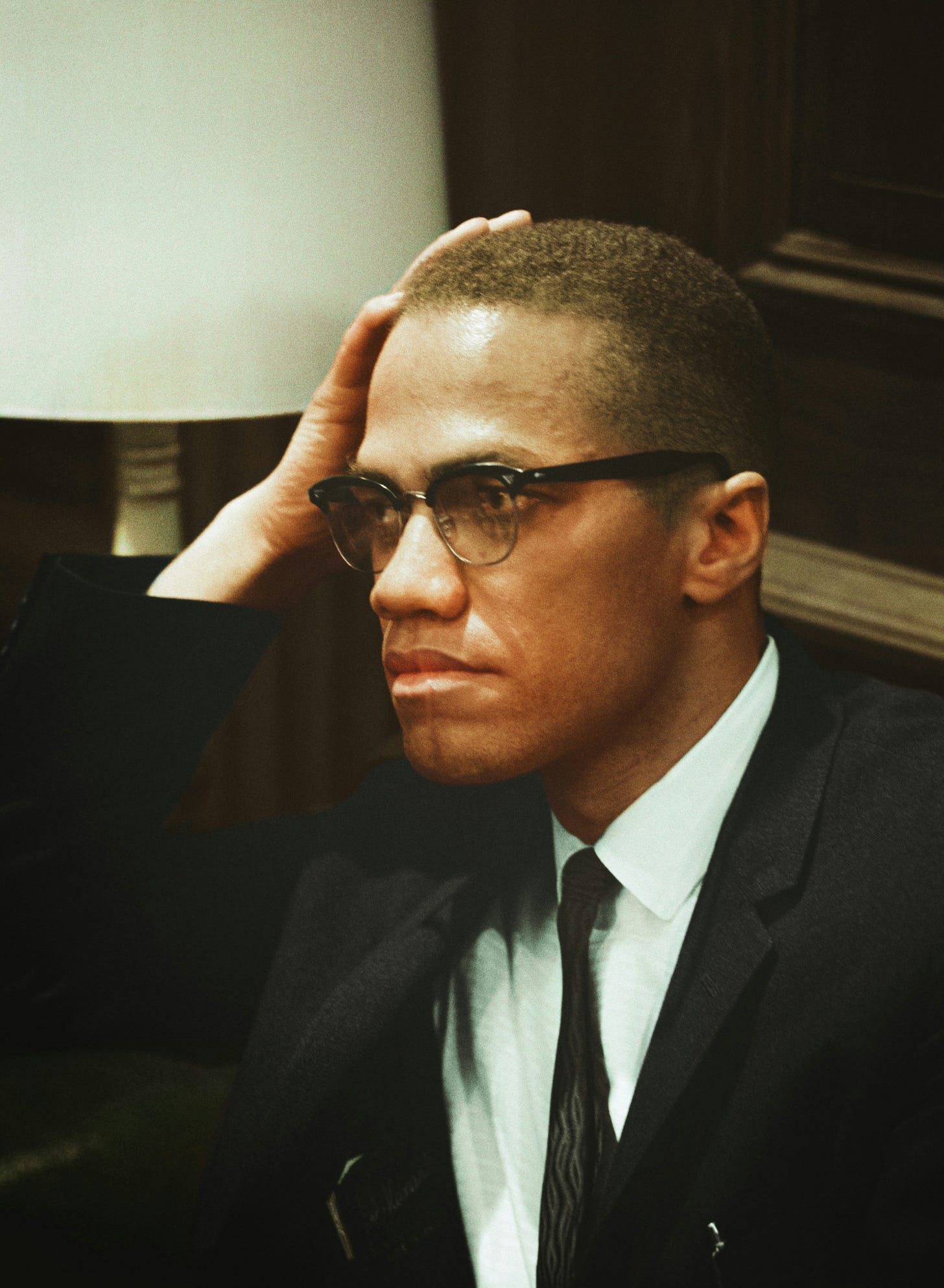

“When we see that our problem is so complicated and so all-encompassing in its intent and content, then we realize that it is no longer a Negro problem, confined only to the American Negro; that it is no longer an American problem, confined only to America, but it is a problem for humanity.” — Malcolm X

It was mid-afternoon when Triest and I arrived at Pappadeaux Seafood Kitchen for our dinner date last Saturday. The packed parking lot was our first clue that we weren’t the only ones with this idea. I hadn’t eaten much that day, so excitement mixed with hunger as I parked.

Inside, the hostess greeted us with a warm smile, but my heart sank when she said the wait for a table for two would be an hour and 20 minutes! Worse, the massive oval-shaped bar was an even tighter squeeze than parking, leaving no room for first-come-first serve walk-ins.

We promptly added a name and number to the waitlist, never discussing the possibility of scrapping our plan for another day. We were committed. We drove 35 minutes to the restaurant because Triest had a $50 gift card, and the food is always delicious. Without kids in tow — and with dining out being such a rarity for us — this felt like the perfect opportunity to indulge.

Only my patience wears thin with traffic, crowds and long wait times. Add hunger to the mix, and I’m liable to turn into a monster. The last thing I wanted was to ruin the moment for Triest with my grumbling.

But as the minutes dragged on, I almost did anyway — just not in the way I ever expected.

To kill time, we hopped back in the car and drove around the community. Before long, we found ourselves in an upscale neighborhood, surrounded by sprawling homes that felt like a distant dream. Each mansion, each manicured lawn, stood as a testament to wealth and success, and I couldn’t help but imagine what it would be like to come home to one of those majestic properties every night.

The first half of our wait passed without issue, just unexpected inspiration. We chatted about everything and nothing, bouncing anything from jokes to ideas off each other like the homies, lovers and business partners we are. Each laugh made and shared thought made the time feel lighter, turning what could have been a tedious wait into an enjoyable moment.

But then my thoughts took over.

As we returned to Pappadeaux’s parking lot, the familiar hustle and bustle greeted us once more. This time, the aroma of fried seafood and Cajun spices wafted through the air, intensifying my anticipation.

In the second half of our wait, we sat in the car, people-watching and imagining all the delicious dishes we were about to indulge in. Triest had the bright idea to pull up the restaurant’s menu online. With another engagement later that evening and so many people dining, it was best to be ready with orders when we finally got a table.

Scrolling through the menu, my excitement quickly turned to surprise at Pappadeaux’s inflated prices. The Seafood Platter, which comes with two fried catfish fillets, shrimp, oysters, stuffed shrimp and stuffed crab, cost $46.95. I still remember enjoying that dish nearly a decade ago — back when it was in the $30 range and I nervously ordered it on my former company’s dime.

Now, two Seafood Platters will run us $100 — no appetizers, no drinks, no desserts. And just like that, we would crack triple digits on dinner.

Suddenly, I started people-watching through a different lens. I fell silent and grew distant, my mind drifting far beyond the menu for the next several minutes. When I finally parted my lips, I had morphed into a different person — no, not a hangry monster, but a heavy-hearted man.

“Is there any saving us,” I asked Triest.

I paused.

“By us,” I continued, “I mean Black people.”

As we sat in the car, I spotted singles, couples, families and groups filing in and out of Pappadeaux. Some left with bags so large they looked like they had just come from a ritzy shopping spree. I counted four other parties waiting in their vehicles, just like us.

In this predominantly white Chicago suburb, the overwhelming majority of Pappadeaux patrons that day were Black. My mind raced to late Black thought leaders such as James Baldwin and Malcom X. With my question to Triest threatening to change the mood on our date, I recalled Baldwin’s famous quote: ‘To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in rage almost all the time.’

I harkened back to “The Autobiography of Malcolm X,” where, in Chapter 15, the often misunderstood revolutionary discussed the very scene unfolding before our eyes.

“Here, again, it is those few bourgeois Negroes, rushing to throw away their little money in the white man’s luxury hotels, his swanky nightclubs, and big, fine, exclusive restaurants. The white people patronizing those places can afford it. But these Negroes you see in those places can’t afford it, certainly most of them can’t. Why, what does some Negro one installment payment away from disaster look like somewhere downtown out to dine, grinning at some headwaiter who has more money than the Negro?” — The Autobiography of Malcom X

Of course, everyone has the right to spend their money however they choose, as long as it doesn’t negatively impact others. Last Saturday, I found myself reflecting not on individual rights but on a harsh economic reality.

Black people sit on the bottom rung in virtually every financial category. As recently as 2021, households with a white householder owned 10 times more wealth than households with a Black householder, according to the United States Census Bureau. There are many reasons this disparity persists, many of them systemic and long-standing.

But blaming is always easier than accepting accountability. Encouraging the masses to commit to lifestyle changes doesn’t evoke the same emotional response as urging them to boycott big-box retailers like Target.

My habits have evolved so much it was impossible for me to not notice last weekend’s disproportionate demographics. It was only the fourth time this year that I’d spent money at any restaurant, and just my second time sitting down to eat. My previous three dining experiences had totaled only $100.91, but Pappadeaux plucked more from me on that sunny Saturday afternoon. After years of self-discipline, however, this rare splurge felt worth every penny.

We dined on fried alligator, a half dozen oysters, crab and spinach dip, fried soft-shell crab, fried catfish fillets, French fries and dirty rice — we really went in! But we opted out of alcohol, which helped save some money.

Dinner totaled $138.74. Thanks to Triest’s $50 gift card, our balance fell to $88.74 — though that didn’t include the tip. Our waiter, Jaime, was just OK, friendly and attentive, but he was slow. He definitely didn’t deserve a $27.75 tip to himself, as the 20% suggested tip calculated.

But for the first time, I viewed my tip as payment to the group that delivered our dining experience — not just Jaime, but also the chefs, busboys, dishwashers and food runners. I left an even $27 for the tip, and I still believe our tipping culture is awful and should be abolished.

I paid $115.75 for our eye-opening Pappadeaux experience.

Yet as I scarfed down seafood from our center table in the bustling dining room, I couldn’t shake the feeling that I was a crab in a barrel.

I gained so much from this Money Talks experience! I recalled so many childhood memories of the pure joy, not of eating out at a fancy White napkin restaurant, but of the rare, very rare times when my parents SACRIFICED to treat us (All 8 of their children) to “TAKE OUT!” No cooking at home; no dishes to wash, no same routine menu. The pure thrill of joining the “Haves” made this “had not black child” realized that there was more to have, more to do, more to be AND it made me work harder to get more for me and for my off springs!

You know all to well that splurging on a single parent household salary was a rarity! And yet, I think like the younger me, my younger four sons did well to be even modestly exposed to MORE! Even to this day, I resent That Pappadeaux (and so many other popular, taste-tempting restaurants) have always been beyond my everyday budget. I don’t believe that my Mother ever ventured into that segment of culinary delight — of course her Cajun cuisine easily equaled or surpassed Pappa and Deaux’s!!

I thank my parents for their modest yet consistent efforts to raise children who were aware that wealth was not to be squandered, but acquired and amassed to provide for their family’s in the here and now and to expose their offsprings to the next levels to which to climb— while giving us the desire, fortitude and abilities to reach for and attain those upper levels.

Thank you for reaffirming the good parenting I was privileged to have received!!

Uneducated money habits with poor discipline are definitely eroding our Black wealth, currently and long term. We must do better to have and be better. But unfortunately, some don’t know or care that they could do more, and that’s the biggest problem.